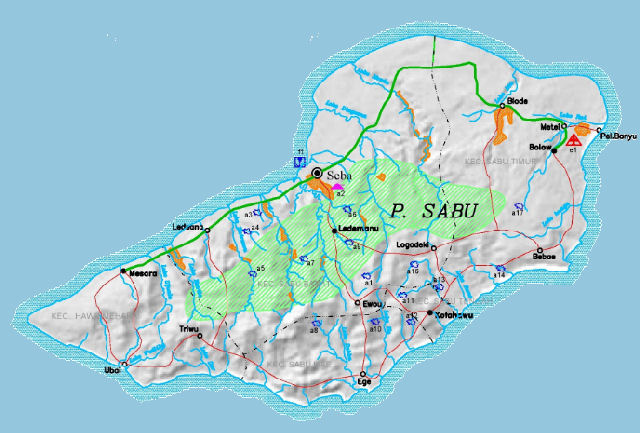

Savu, the island with visual appeal as its hallmark

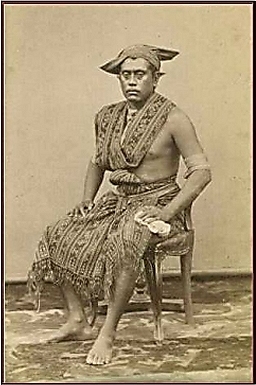

Savunese school kinds photographed in 1961. Photographer unknown. Re-photographed by Georges Breguet at Geneviève Duggan's exhibition in Museum Tekstil, 2013. Savu is an attractive subject to write about, because the island itself, the people, and their textiles have an instant visual appeal. Yet it is also hard to write a short piece about it, because it has been dealt with so exhaustively by two researchers, James J. Fox and Geneviève Duggan, who both spent a considerable time there and studied every aspect of life, material and immaterial, on the island. It is hard to do their work justice within this confined space. Those who have more than a passing interest in the island should definitely slake their thirst straight from the source, Fox's Harvest of the Palm, very enjoyable reading also for laymen, and Duggan's more esoteric but still eminently readable Ikats of Savu (see Literature section). In literature, Savu is invariably described as a beautiful island with charming people, and its ikat textiles with their warm tonality and high quality weaving have an immediate visual appeal. The same applies to its smaller neighbor, Raijua. When the celebrated Captain Cook returned from his first successful exploration of the Pacific in 1770, he stumbled upon Savu, a mere speck in the ocean halfway between Timor and Sumba. It was pure luck, because, as he noted in his journal, the island was "so little known that I never saw a map or chart in which it is clearly or accurately laid down." He also note that the island had "a most pleasing prospect from the sea."

Probable Indian/Hindu originsThe Savunese, currently numbering around 30,000, look very different from the inhabitants of neighbouring islands, more similar to people of Indian stock. The great naturalist explorer Alfred R. Wallace (he of the Wallace Line between Bali and Lombok that separates the Asian from the Austronesian fauna) wrote of his 1868 visit to Timor in The Malay Archipelago: "I saw in Coupang some chiefs from the island of Savu further west, who presented characters very distinct from either the Malay or Papuan races. They most resembled Hindus, having fine well-formed features and straight thin noses with clear brown complexions. As the Brahminical religion once spread over all Java, and even now exists in Bali and Lombock, it is not at all improbable that some natives of India should have reached this island, either by accident or to escape persecution, and formed a permanent settlement there."The Savunese themselves claim Aryan Hindu origin, and have strong historical ties with Javanese Hinduism. There are continued speculations that the Savunese are descendents from refugees of the Majapahit Kingdom on Java, who fled Islamisation when their empire crumbled under the emerging Muslim forces in the middle of the 16th C. Unlike Bali and Lombok, on Savu there is no trace any more of Hindu religious practices. By co-opting local rulers, Dutch officials and missionaries in collusion introduced Protestantism, which remains the dominant religion on the islands today, but the Savunese also still perform traditional animistic beliefs, known as Djingi Tiu, which they have managed to integrate in their form of Christianity. Savu ikat textiles - communicating the unspeakableSavunese society, in many respects very conservative, is made up of several udu, groups of localised male origin who play an important role in political and ritual life, but have little or no import on the ikat textiles produced, and of two non-localised hubi, matrilineal clans, Hubi Ae and Hubi Iki - commonly translated as Greater Blossom and Lesser blossom, though according to Tali and Von Reinhaart who maintain a website on Savu and Raijua (see Links), the terms do not imply a difference in rank or other value differences. These two clans are both subdivided in a number of wini, or 'seeds'. Inter-hubi marriages are not proscribed, but discouraged. Preferably, Savunese will even marry within their own wini.

For their sarongs, all women of Hubi Ae have in common the wo kelaku, a group of motifs in the shape of a lozenge (third from the top in the table), which appears in four variations. All women of Hubi Iki have the serpent like motif ei ledo in common (third from the bottom), also in several variations. The Savunese sarongThe traditional woman's wear on Savu, as on all the islands of Nusa Tenggarara Timur, is a long tubeskirt or sarong, on Savu called ei, which normally falls to the ankles. At formal occasions the sarong is pulled up high, over the breasts to the armpits, and tied at the right hand side (the left side being reserved for the dead). For walking a long distance, the sarong may be pulled up to the knees, but before entering a village it will be pulled down again to the ankles. In larger towns where modernity has made inroads, the ei may nowadays also be worn as a skirt with a blouse.Savunese man's wearMany Savunese men nowadays wear commercial sarongs of Javanese or Buginese model of thin cotton, or trousers and shirts. But for formal occasions the traditional stole is prescribed: a rectangular cloth wrapped around the hips called hi'i (a type of cloth that elsewhere in Indonesia is called a selimut) and ideally a second one worn over the shoulders (in the manner of what elsewhere is called a selendang). The most traditional hi'i displays just two colours, indigo and white, in the ikated bands of motifs, and called the 'black loincloth', though the colour may vary between light blue and almost black indigo. Loin cloths (to stay with this word, though the Savunese men use it also as shoulder cloth) displaying three colours in the main band are called worapi. The loin cloth is made up of two uneven halves, the larger half symbolising the older sibling (bahasa: kakak), the other the younger sibling (adik). There is much less variety in men's hi'i than there is in the women's ei, and none of them are related to the patrilineal udu groups.Followers of the original Savunese religion, Jingi tiu, which in many cases is adhered to in conjuction with Christianity, maintain strict observances about who can weave their loin cloths. A wife may weave him a cloth for ritual use only if she belongs to the same wini, or at least to the same ubi. If he has married outside his wini or even his ubi, then a sister or another woman from his progenitric line will have to do the weaving for her - certainly if the cloth in question is to be his last one, the one in which he will buried. These rules are discarded by families where Christianity has become the dominant force, and are likely to be less observed as tradition fades away into faceless modernity - a time when ancient motifs, once rich in meaning and social value, serve for decoration only.  | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||